Reports: UR955347-UR9: Computational Studies of Osmotic Membranes for Petroleum Wastewater Reclamation

Mingheng Li, PhD, California State Polytechnic University

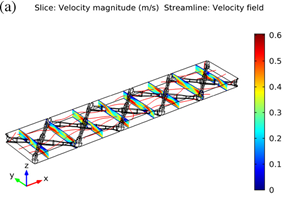

Fig.

1. Contours

of velocity magnitude on eight yz-slices and streamlines in (a) spacer-filled

channel and (b) unobstructed channel.

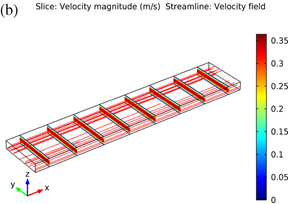

Fig.

2. Streamlines

(v, w) on three yz-slices in spacer-filled channel. The slices are cut

In

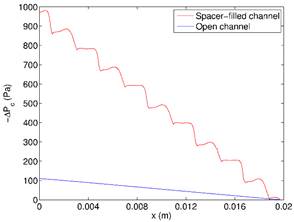

industrial BWRO operation, the average longitudinal velocity of the retentate

stream gradually reduces as it travels along the pressure vessel due to water

recovery. To develop a system level model for pressure drop, a parametric

analysis is carried out by varying velocity at the inlet of the computational

domain. The pressure differential is recorded and compared with correlations of

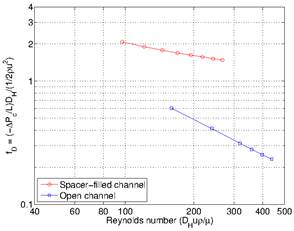

channel flow. The Darcy friction coefficient is calculated as follows:

(1) In the flat narrow channel the 3D numerical simulation matches

closely with the theoretically derived relationship fD=96/Re.

However, in the spacer-filled channel, fD is several times larger if

the Reynolds number is the same.

Fig. 4. Darcy friction coefficient vs Reynolds number.

.

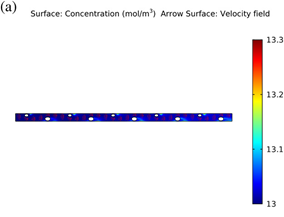

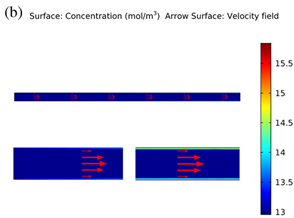

It is found that in the spacer-filled channel Salt concentrations and flow arrows are plotted on an

xz plane for both the spacer-filled and unobstructed channels, as shown in Fig.

5(a). It is observed that concentrated islands

are isolated in zones near the spacer filaments, where the flow is stagnant.

These are areas associated with smaller fluxes. The concentrated region is

thinner in regions with high fluid velocities. The concentration polarization

profile in spacer-filled channel differs from the one in the empty channel,

where a concentrated layer gradually develops along the channel severely

reducing permeation flux. Fig. 5. Salt

concentration with fluid flow arrows on xz plane of (a) spacer-filled channel

and (b) unobstructed channel.

The mass transfer coefficient km is related

to salt concentration gradient at the membrane wall by the following equation:

(2) Using the concentration gradients reported by the

converged CFD solution and Eq. 2, the local mass transfer coefficients in the

computational domain based on four different values of inlet velocities are

calculated. This is because as water permeates through the membrane, the

average longitudinal velocity decreases in a long pressure vessel, leading to a

reduction in km. It is seen that km reduces with respect

to both location and longitudinal velocity in open channel. For the

spacer-filled channel, km reduces mostly with respect to

longitudinal velocity. However, at a given velocity, it appears that km

profile is repeated from cell to cell and there is no significant decay in

cell-average km with respect to location.

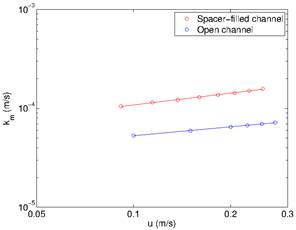

The cell-average km over the

length of five unit cells is calculated and it plotted as a function of

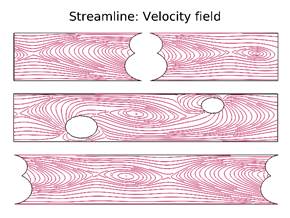

Fig.

3. Pressure

differential along feed direction with average feed velocity of 0.25 m/s. The

x-axis is a horizontal line cut at y = 1/4 width and z = 1/2 of the

computational domain.

![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

![]() on

a loglog scale, as showed in Fig. 6. Both follow straight lines, however, the

slopes and magnitudes are different. In the open channel,

on

a loglog scale, as showed in Fig. 6. Both follow straight lines, however, the

slopes and magnitudes are different. In the open channel, ![]() ;

the power law index is very close to 1/3 as indicated by the boundary layer

theory. In the spacer-filled channel,

;

the power law index is very close to 1/3 as indicated by the boundary layer

theory. In the spacer-filled channel, ![]() .

The existence of spacer filaments significantly enhances mass transfer.

.

The existence of spacer filaments significantly enhances mass transfer.

Fig. 6. Cell-average km as a function of average feed

velocity.