Guidelines for Prospective Organizers of an International Chemistry Olympiad (IChO)

- Introduction

- General timetable for organizers

- Necessary amenities

- The work of the Scientific Committee

- Day by day organization

- Sample documents

Introduction

This page describes to Potential Organizers of an IChO the recommendations and suggestions that reflect current (and hopefully best) practice. However, the formal and official rules are contained in the Regulations of the IChO from the Information Centre. All organizers should be familiar with these official regulations as well. While the information refers to and elaborates on the Regulations of the IChO, these suggestions are not part of the Regulations and they are not binding to either party. If these suggestions are difficult to apply in practice, or there is a better way of doing things, then the matter should be discussed by the organizers and the International Jury.

The guidelines are based upon the work by Jan Apotheker (organization chair of the 34th IChO), the reports of the working groups in Warsaw, Neusiedl and Smolenice and a 2003 Hungarian proposal. This version was compiled by Gábor Magyarfalvi. The most recent update was done according to the suggestions of the Steering Committee meeting in Ankara in December 2010, with further editing by Bryan Balazs.

The guidelines should be edited and updated regularly so that future organizers can use it, and it should be made available to all interested parties.

General Timetable for Organizers

Before application

The fundamental question to be asked before considering whether to host an IChO is whether there is enough support available to host this event. Organizers are responsible for gathering this support, and support can come from organizations within the host country such as:

- Ministry of education

- National chemistry society(ies)

- University(ies)

- Chemical industry(ies)

- National (chemistry) teachers association(s)

Prospective hosts should apply at least 3 years in advance, submitting a proposal letter to the steering committee (this letter must list the contact person of the prospective organizers).

Finances

The cost of organizing the IChO depends, among other things, on the country where it is held and the number of participants. For example, Germany had a budget of 1,400 k€, Korea 2,500 k$, Russia 3,000 k$, Hungary, 1,000 k€, and the United Kingdom, 910 k£. Prospective hosts must have adequate financial guarantees before applying to organize an IChO, and it is the responsibility of the host organization to insure that these financial guarantees are in place.

Venues

Before formulating an application to host an Olympiad, the venue to be used for the practical examination must be clearly established. With the growing number of student participants, (240 in 2003 increasing to almost 270 in 2010), sufficient lab space is an important consideration. Efforts must also be taken to insure that the individual lab spaces (and any needed equipment) are as equivalent as reasonably possible.

Sufficient accommodations for students and mentors must also be available, and these accommodations must be separated by a distance sufficient to insure that chance interaction between mentors and students is not possible once the exam is underway. Each country typically sends 4 students. The number of people accompanying the students (Mentors, Observers, or Guests) averages about 3 per country.

Organization

It is necessary to have a reasonable number of people within the institution that will serve as the base for the activities. The chair of the Olympiad should be affiliated with that organization in some form.

Several committees need to be formed:

- an organizing committee, with a number of people responsible for different tasks. Each of the subcommittees is represented on this committee. This is the committee that is formed first and the committee that makes all of the decisions.

- a scientific committee, responsible for the preparatory and competition problems and exam marking (grading).

- a support committee, This committee has no function other than endorsing applications for financial and other support. Members may be local mayor, governor, national minister or president, royalty, university rector, Nobel Prize winners, etc.

Year minus 3

At this point, the application to the steering committee has been accepted, and the chair of the organizing committee is now a member of the steering committee. He or she should report in the December meeting of the steering committee on the initial progress of the organizing efforts.

At this time there should be:

- A firm commitment of financial support

- A definite venue for the practical exam and theoretical exam

- A chair of the scientific committee

- An organizing committee

- A tentative timetable of the IChO (See suggestions in part 5).

Year minus 2

By this time, the needed venues (for ceremonies and other such events) should be reserved. The scientific committee should have started its work on the exams and preparatory problems. The logo of the Olympiad should be decided upon. Decisions on the excursions need to be made. Most large scale activities and venues will be available about two years ahead of time.

Contacts should be made with the government, and verification should be made as to which officials or royalty will be present during the opening or closing ceremonies. Membership of all committees must be established.

Year minus 1

During the Olympiad occurring in this year, the future organizers distribute the first issue of their Catalyzer. They receive the flag of the Olympiad at the closing ceremony. The website of the future Olympiad should be live.

Registration is organized through the head mentor for each country. Therefore, the organizing committee must know the contact details of this person. This can be done either by sending them a letter in September (see sample 1 in the “Sample Documents” section of this document), or by canvassing countries at the prior Olympiad.

The head mentors receive an invitation by December (see sample 2). In a number of cases, as requested by the mentors, an additional invitation must be sent to the ministry of education or the national chemical society in order for them to facilitate their travel arrangements. The mentors should respond by returning the following:

- The names of the adults accompanying the team ASAP (see sample 3)

- The names of the team participants (see sample 4)

- Their travel schedule (see sample 5)

By September, the first draft of preparatory problems should be ready.

In December a Steering Committee meeting is hosted and the major venues (laboratory and classroom spaces, ceremonies, accommodations, etc.) are presented and discussed.

Year of Hosting

The preparatory problems without the worked solutions are published on the Internet in January. Two hard copies with solutions are sent to each head mentor, but there is precedent for a simple posting via e-mail. The current regulations including the syllabus should either be included in the problem booklet or published on the website. After distributing the preparatory problems with solutions to the head mentors, the host should launch and moderate a special webpage of the Scientific Committee for receiving comments and corrections.

By January it should be clear what glassware, chemicals and solutions are needed during the practical exam. By May the final version of both exams should be ready and tested. By June the organizers should receive the travel plans and the names of the students. Organizers will need at least two weeks to prepare the labs for the practical exam.

During the Olympiad, organizers must provide for three groups of participants:

- Students (4 per country) + 1 guide for each team.

- Mentors and scientific observer(s) (maximum 4 per country).

- Paying guests at the discretion of the organizer (about 5% of the mentors and observers).

These individuals include the observers from future organizers. Some countries prefer if they are called observers instead of guests.

Post Olympiad

A final report must be prepared and should be distributed to all participating countries or published on the Internet.

Necessary Amenities

The Catalyzer

An editorial board is needed for the Olympiad newspaper, the Catalyzer. This board may also create other publications. During the Olympiad, a photographer and several writers will be required.

The Catalyzer should appear daily during the Olympiad and may contain news about the student participants and their excursions, articles relevant to chemistry in the host country (famous chemists), jokes, birthday celebrations, etc. The last Catalyzer contains the allocation of the medals and should be available at the closing ceremony. The Olympiad is a competition between individuals, not countries, so country rankings are not included in this document.

One of the Catalyzers (or a separate document distributed to every participant) should contain the contact information of mentors, observers, and students.

Guides

A guide who stays with the students at all times is needed for each country’s team. Generally it is advisable to use a guide who speaks the same language as the students. Most often the guides are university students affiliated with the host organization.

Lab assistants

These individuals assist during the lab exams. It is necessary to have about 1 assistant for every 8 students. Lab assistants should be aware that they may not necessarily have a common language with quite a few of their students. However, there should not be a need for communication with the students except in the case of an emergency.

Buses

Transportation can be facilitated if people are assigned to the same bus throughout the Olympiad. In addition, it is helpful to have a host person responsible for each bus.

General assistants

In the mentors’ accommodations, helpers for all sorts of tasks (5 persons or so total) come in very handy.

Backpack and materials

It has become customary to give all participants a bag or backpack, containing general information, a T-shirt, a notepad, writing equipment, and a calculator. The latter are to be used during the exams. This way the checking of the calculators is avoided. The pens should leave a mark that makes visible copies.

Badges

All participants will be given, and should wear, a color-coded badge, with their name, their country and their function (student, mentor, observer, etc.). These badges may also contain a small program summary for the Olympiad (typically inserted into the plastic holder along with the badge). The badges for the students should indicate their code e.g. NL-1, US-2, etc. A good idea, which was started in Cambridge, is to list on the badge the individuals preferred form of address, or “nickname”; this preference must of course be determined in advance before the badges are printed.

Catering

Care and discretion should be taken with all meals. Because the standard diet of the participating countries differs tremendously, and for some religions, there are food restrictions, a variety of food choices should be served. It is also important to follow generalized cooking conventions in terms of the degree of “doneness”, especially for animal products. It is important to label the content of the foods served. Pork and beef is not always suitable for everybody, and vegetarian food should be made available. The breakfast choices should suit both Western and Asian diets.

Computers

Computers are made available for each country to translate the final text of each exam into the language used by the students. Teams using a common language usually cooperate, and it is useful to find out about the cooperation beforehand and distribute the computers according to language commonalities.

Computers should use Windows and Microsoft Word. The programs required to edit schemes, diagrams and structures should also be available to allow the translation of the captions, but it is advisable to avoid text in the figures and schemes. If a country has special requirements, like an azerty-keyboard, they have to bring this equipment. A special team that can help in case of computer problems should be available.

If only a single computer is assigned for a particular language, translators (mentors and in some cases observers) should be allowed to use their own laptop computers. The delegations should be informed beforehand if they can /cannot use their own laptops.

Networking the computers is not necessary (the risk of viruses and worms is high with laptops and media from all over the world), but there will be a need for local connections to printers in order to print rather large volumes easily.

Copying facilities

As many as 50000-100000 (105) pages of paper could be used during the Olympiad. High-speed copiers (with backup) and enough personnel are necessary to meet the tight deadlines. Avoid stapling and low quality paper (for auto-feed).

The Work of the Scientific Committee

Membership

In the past, chemistry professors of the organizing country have chaired the committee. The members should be academic staff in different fields of chemistry each with an excellent command of English. An experienced mentor must also be a member of the Scientific Committee. This person would make sure that the problems generated by the committee comply with the Regulations of the IChO.

Timetable

The Scientific Committee should have at least two years to work on the exams. Its members should be aware of the nature of the Olympiad and their role during the Olympiad. The importance of this insight can't be overemphasized due to the unique nature of the competition. The role of the Jury and the importance of the Jury sessions must also be emphasized. Typical IChO problems are different from the textbook, classroom or exam problems that educators typically use. During the two years that the Scientific Committee is functional, there should be regular contact between this committee and the organizing committee.

Preparatory problems

The preparatory problems come with worked solutions, but the solutions are initially sent to the mentors only. Some countries request that the official solutions not be published to the general public (Internet) until the end of Olympiad so that they can use the problems in their exams.

Do not underestimate the work required to prepare a consistent problem set. The participating countries scrutinize the preparatory problems in detail, as this is their main source of information before the Olympiad. The committee should take care that the examinations and the preparatory problems are consistent with each other and the regulations. It is generally a good idea to have the outline of the exam problems ready before starting work on the preparatory problems.

Special care should be taken about the number of advanced topics in the preparatory problems. There is a maximum of 6 theoretical topics and 2 practical skills allowed here. These should be listed separately and each should be included in at least two problems.

It is not desirable when other advanced fields remain in the preparatory problems without explanation (e. g., hidden in a sub problem), because many countries will try to cram in training in those fields. Authors should be reminded that these advanced topics are introduced to most students in a very limited time. They will still be high school students, not experts (e. g., their dexterity in the lab, their spectrum interpretation skills will still be limited). The problems should require more thinking than preparation.

Any factual info (e.g., chemistry of an element or a specific reaction type) that is needed in the exam should also come up in the preparatory problems as well.

Practical exam

The laboratory procedures, i.e., “recipes” of the practical should be tested thoroughly and prepared with secondary students in mind, and all experiments should be thoroughly checked under the conditions that will be experienced during the actual practical examinations at the Olympiad. It is advisable to have more than one qualified person perform the experiments during the exam as well.

When considering the quantities that are to be supplied and the time to be allotted to the tasks, remember that the competitors are high school students who are generally inexperienced lab workers. The length of the exam should be such that most students will have time to attempt to work through all tasks. Theoretical questions in the practical, if any, should pertain to the essence of the experiment.

Every effort must be made to ensure that individual sets of equipment and workplaces are as equivalent as possible.

It is possible to have split laboratory sessions. That is, a morning session and an afternoon session can be held for all. Alternatively, laboratories can also be rotated in two sessions. The reservations associated with the latter system are that students must be strictly separated and that the organizers must insure that the equipment has been properly cleaned, dried, and redeployed if it is being reused.

Labels on containers in the lab should use chemical formulas, not names, where possible. If there are reagents for the common use of students, care should be taken to avoid cross-contamination. Common use of equipment or other materials should be avoided if possible but, if there is equipment for common use, a system should be in place that minimizes waiting time and provides fair use (e. g., a sign-up list monitored by supervisors).

There have been problems in the past with the time required for the drying of a product, or with melting point determinations. Sometimes this issue has been resolved by lab staff making the measurements after the students have finished the exam.

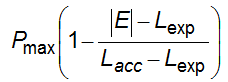

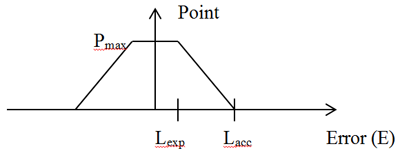

A scheme should be constructed for grading experimental results that is based on results obtained during testing of the practical. A suggested solution that has worked well in the past:

- Full marks should be awarded if the result is in a range that reflects the values expected by the examiners. The expected theoretical value must come from the analytical procedure performed on the exam day.

-

No marks should be given to results outside the limits of acceptable values.

Both ranges, expected and acceptable should reflect the examiners experiences. - Between these two, a linear scale should be applied.

| Numerically: | Pmax points, | if 0 ≤ |E| ≤ Lexpected |

| 0 points | if Laccepted ≤ |E| | |

|

if Lexpected ≤ |E| < Laccepted | |

| (Pmax – maximum points, E – error, L – range limits) | ||

| Graphically: |

|

|

Typical values for a titration would be

Lexpected = 0.5% relative error in the volume.

Laccepted = 3 % relative error in the volume.

Ranges need not necessarily be symmetrical. For example, the accepted range above the true melting point should be rather narrow.

Students should be allowed to decide on the number of parallel measurements (titrations) they make. Only the final value (probably a mean) as reported by the student should be graded. Marks should depend on experimental values, but not on precision. (This is based on the fact that students may make up concordant results.) The emphasis should be on marking practical work, therefore the results should be recalculated uniformly.

Errors in the calculations should invoke a minor penalty, the magnitude of which should be suggested by the organizers and approved by the International Jury. Serious mistakes in applying the rules of evaluation of experimental errors can be penalized (e.g., the number of significant figures differs in more than two digits from the correct, rounding errors exceeding accuracy). The magnitude of the penalty should be suggested by the organizers and approved by the International Jury.

Students can be penalized for asking for replacement samples or additional reagent(s). The practice in past Olympiads was that after the first request there was a penalty of 1 of the 40 available practical points for each subsequent request. Students may also be penalized for not strictly following safety guidelines.

Theoretical exam

The authors should remember that the contestants are high school students. The tasks should focus on using the fundamentals of chemistry in a unique way that requires thinking. The emphasis should be on chemistry, not on mathematics. The length of the exam should be such that students will have time to attempt to answer all questions. There should be a balance between the classical areas of chemistry in the problems. The final weights of the individual problems in the marking should reflect their difficulty.

Unless an exam question specifically gives guidance on the use of significant figures for that question, the number of significant figures in the theoretical part is generally not marked (graded). This is because many members of the Jury like to point out eventual inconsistencies, causing endless discussion in Jury meetings and arbitration.

Marking and arbitration

A detailed marking scheme should be presented with the exam to the International Jury. Points for partial solutions are best decided by the organizers using common sense during correction, and they should be awarded uniformly as all possible errors can not be pointed out beforehand. For example: If the question is to provide a balanced chemical equation, then partial credit should be awarded to those who correctly identify the reactants and products, but fail to balance the equation correctly. The Jury should only discuss partial marks in the most critical cases.

Students are asked and are expected to show their work. This will help in awarding partial marks; however there should not be a penalty for failing to show each and every minute step clearly, as long as the results are correct. That is, if a student omits some, possibly trivial steps, or uses a different solution, she should receive full marks, if the results explicitly asked for are correct. However, if only the final result of a complicated problem is given but without any supporting explanation, no points are awarded.

All attempts should be made to minimize carrying over results between questions; in other words, obtaining the correct answer for one question should not be necessary to correctly solve a subsequent problem. Thus, consequential marking should be used, that is: full marks should be awarded for a question if the student solves it correctly and consistently using a faulty result from another question. There is no double penalty (often referred to as “double jeopardy”). Often this is an issue in Jury meetings.

Positive grading, in which points are added for correctly answering individual aspects of a particular task, rather than negative grading, in which points are deducted for errors, is usually more helpful for a smooth arbitration process.

A discussion during Jury arbitration is usually unavoidable and sometimes can become quite heated. The situation should be handled tactfully: mentors are usually quite competent professionals even if their command of English may not be perfect.

Responsibilities of the authors of the problems during the Olympiad

- The authors of the experimental tasks must present safety information to the students prior to the practical exam. This must include the demonstration of the use of equipment that is unfamiliar to most high school students, keeping in mind that the demonstration must primarily use gestures and universal signs, as many students will not understand English.

- The authors of both the experimental and theoretical problems must be present for discussion with the mentors before the Jury sessions. They must also attend the Jury session during the discussion of their problem.

- The authors must be available during the exams to solve any unforeseen problems.

- After the examinations, the answer sheets must be copied at least two times. One copy is marked by the authors, the other by the mentors. The original must be kept safe. During arbitration it must be made available if required.

- The authors mark (grade) the answer sheets. After arbitration, the marks are final. Grading takes a lot of time as does recording of the individual scores of the students. Care should be taken that the name and the code for the student are unambiguous. The final scores must be made available for the mentors for a last check.

- The scientific committee checks the grades and determines the cutoffs for the medal allocations. The Jury makes the final decision without knowing the exact scores, typically at the first sizable point gap under the maximum number of medals according to the Regulations.

- Extra prizes can be given for the best theoretical work and for the best practical work, but an extra prize for the best female student is not recommended.

- During the closing session, the chair of the scientific committee presents the results of the exams.

Day-by-day Organization of Program Items

Day 1

Arrival of guests

The organizing committee is responsible for the transport of participants from the international airport(s), or other official arrival locations, to the venue of the IChO. Any means of transportation may be used. Participating countries should supply a time schedule of the arrival of their delegations. Delegations should not be kept waiting too long at the airport.

Hotel accommodations must be available for delegations that arrive early or leave late. However, those delegations must themselves cover the additional cost.

Registration

All participants receive a badge with their name, country and their function (student, mentor etc) indicated. These badges are expected to be worn throughout the event. Before handing out the badges and other material, the identity of the team members should be checked against their passports. The list of mentors and observers should be distributed.

Problems with travel documents

The organizing committee should check beforehand with the government agency that is familiar with the visa requirements for different countries. Generally an early discussion, i.e. two years before the event, should facilitate sensible agreements between the appropriate agency and the organization. A contact person in the visa department is very handy in case of last minute problems.

Health requirements

Delegates must have health insurance, and this should be checked at registration. Generally, recommendations of the WHO should be followed when health or disease situations arise, such as the SARS crisis during the past Greece Olympiad. A signed document by the head mentor, stating that all members of his team are insured, should suffice.

Academic code

Each delegation is expected to sign an academic code that includes compliance with IChO Regulations and a voluntary communication ban between students, mentors and observers during critical parts of the competition. Checking compliance should be at the discretion of the organizers. Examples of past Olympiad practices: In Groningen mobile phones for both the mentors and the students were collected, and in Athens, the organizing committee collected the students’ phones.

A welcome dinner is customary on this evening.

Day 2

Opening session

The opening session must be planned well beforehand, particularly if it is desired that officials at the national government level participate. These individuals will need to be asked at least a year in advance, although keep in mind that the plans of these officials can change at the last minute, and a backup plan should be available. Invitations should also be sent to the embassies of the participating countries, and to other appropriate dignitaries.

An awareness of sensitivities between countries is critical. China and Chinese Taipei/Taiwan is a prominent example. It is wise to check the arrangements with the ministry of foreign affairs, as they have a protocol department that can provide advice.

During the opening session, the teams are presented. In some Olympiads, the students have carried their country’s flag or had an image of the flag projected on the screen. In Bangkok, photographs from each country were used.

After the opening session, a lunch (possibly with a reception) is usually provided for the participants.

At this point, students must be separated from the mentors and observers until both exams have been completed. From this point on, the two groups have different programs as outlined below.

The mentors program

After the lunch following the opening ceremony, the mentors are taken to the laboratories where the practical examination will take place. They check that the equipment at each workspace is complete and in good order. The positions in the laboratory must be labeled with the code of the student that will work at that position and a plan indicating the place of each student must be available so that the mentors can find their students.

After leaving the laboratories, the head mentor receives 2 copies of the practical exam and the mentors are transported to the venue where the 1st Jury session is to be held.

The discussions in this Jury meeting can be shortened considerably if the delegations can study the problems and have an opportunity to discuss them individually with the authors before the full jury meeting. Many of the issues that mentors may have with the tasks may be resolved in one-on-one discussion with the authors before the task is discussed in the entire international jury.

During individual discussions and before the jury meeting, delegates should be informed of the changes the organizer intends to make based on the discussion, e.g., a copy listing the changes posted on a notice board during individual discussion, then a printed copy for the full jury meeting. This system is recommended for both the theoretical and practical exams.

After the scientific committee has had a chance to discuss the changes suggested by the mentors, the 1st Jury session can begin.

Jury sessions are conducted in English and the command of English of many of the participants is not sufficient to effectively present, argue, or debate the relevant points. Thus, it is important to have a strong AND fair chair at these meetings. The most successful Jury meetings in the past have been those where the chair allowed the various points to be discussed, insisted on firm written proposals for changes, presented these in a form which everybody could read, and then called for a vote. Once the vote has been taken, the item was not discussed further.

The Chair of the Scientific Committee, who presides over Jury meetings in which exam questions or marking are discussed, should have enough experience with the IChO and mentors in order to have a full understanding of issues arising and the mentors’ point of view. There may be merit in having a co-chair who is an experienced member of the Steering Committee or the Jury.

The Jury sessions may be exhausting, but it is critical that the correctness of the competition tasks be open for discussion and that the authors are prepared to accede to suggestions based on experience at previous Olympiads. Correction of phrasing and English spelling should be raised in a Jury meeting only if these changes are necessary to properly convey the meaning.

During the Jury session, an overhead projector or a computer having the screen projected is the easiest way to discuss the different text proposals. The computer operator should be a person proficient in English and familiar with the problems. Microphones must be available for all speakers from the floor, and the meeting chair must insist that these be used.

Voting should be carried out carefully. Resolutions and options to be considered should be presented to the Jury very clearly (in writing if possible). Conformance with regulations (75% presence, majority vote) should be checked. Results should be announced to all delegations.

At the end of the discussion the final exam text, marking scheme (blue points) and problem weights (red points) should be introduced for acceptance. Once the final text of the exam is agreed upon, this document is made available to the mentors of all of the participating countries. The final versions of the translated exams must be handed in by the head mentor. The scans of the various exams are made public on the Internet as a check of the translation quality and its adherence to the original text.

The computer network opens at the start of Jury session 1 and closes at midnight. The next day, it reopens as soon as the mentors arrive.

Day 3

This is the day set aside for translation. The host country should resist being persuaded to make changes beyond those decided upon in the 1st Jury session.

Computers should be made available for each country to translate the final text of each exam into the language used by their students. Teams using a common language usually cooperate, and the organizers inquire about the cooperation beforehand so that they can distribute computers accordingly. Because a number of countries are finished fairly soon, it is possible to organize a small excursion towards the end of the day.

Day 4

This is a day of excursion for mentors and guests. The mentors should arrive early to receive the copies of the theoretical exam (2 per nation). It has worked well in the past to provide time for the mentors to study the exam for several hours and give them a chance to meet with the authors individually. See above.

The revisions made during the discussion should be available to all teams. At 20.00 the 2nd Jury session should start. For the theoretical exams, a split session has become the norm; that is half of the problems are considered in one room and the other half in another. The computer room should be opened at the beginning of the Jury session to allow preliminary translation to begin. After the text of the final exam has been approved by the Jury, it should be put on the network. Any further changes should be avoided as much as possible.

Day 5

The translation session for the theoretical exam usually starts around 09.00. Most countries will be finished by 17.00. This is a convenient day for the Steering Committee to meet.

Day 6

During Day 6, the mentors and observers are totally free. They can be taken on an extensive excursion (Amsterdam in Holland, the boat trip in Greece) with the observers and guests. In the evening, it has become a custom to have a reunion dinner, when students and mentors meet for the first time since their separation earlier on. After the reunion dinner, the head mentor receives a copy of the answer sheets of the students with the final grading scheme. (Before the actual exam, only the preliminary solutions are distributed, and only in printed form.)

Day 7

Even though the mentors are required to mark the exams, there is ample time for an excursion. In the evening, the 3rd jury session takes place. The agenda for this meeting, referred to as a “business meeting”, is prepared by the Steering Committee. This meeting can be merged with the medal-awarding 4th Jury meeting.

Day 8

On this day, it should be arranged so that head mentors can pick up printouts with the detailed results of their students as graded by the scientific committee at the beginning of the arbitration. This will save time, since mentors will have a chance to compare the points beforehand and see which tasks require discussion with authors (all the other exam tasks should be just signed off if there are no issues).

During arbitration, the grading of the student exams by the scientific committee and the mentors is compared. In the past, it has worked well to have different sessions, each involving 12 to 18 countries. The members of the scientific committee handle the arbitration for their own question. There is a time limit put on the discussion for each question, but in difficult cases, the delegation should be asked to return later. In cases where no agreement can be reached, the chair of the scientific committee has the final word. If a delegation still disagrees, appeal to the Jury is possible. This appeal must be resolved before allocation of the medals. The marks can not be changed after a given time, and the final marks should be made available to the delegations prior to the 4th Jury meeting.

In the evening of Day 8, the 4th Jury session takes place. The first item on the agenda is the allocation of the medals. This is done on the basis of a merit list presented on screen in a format which makes it impossible to correlate the numbers on the screen with individual student marks. The rest of the evening is used for the continuation of the business meeting, if necessary.

Day 9

The closing ceremony usually takes place at a special venue. See the remarks on the opening sessions. The program of the closing ceremony has a number of set items:

- Discussion of the results by the chair of the scientific committee

- Awarding of the medals. The medal ceremony starts with the honorary mentions, then bronze, silver and gold medals in that order. The best three overall scores are mentioned separately. The organizing committee must be aware of the Regulations with respect to the number of the various types of medals that are awarded.

- The handing over of the IChO flag to the next organizer is done at the end of the ceremony. The representative of the next Olympiad is also allotted some speaking time.

In addition to the above, there are usually some cultural events, and the ceremony is usually followed by a farewell party.

Day 10

This day typically involves the departures of all of the delegations. The organizing committee should help with any necessary travel issues. Note that some teams depart quite early, sometimes right after the closing ceremony on the previous day.

The students program

The students need some time to prepare for the exams, although some getting-to-know-each-other activity is usually organized. A variety of excursions are desirable, some cultural, some scientific and some amusement park type activities. Students also appreciate a bit of free time. The students should be given information on public transportation

Day 2

After the opening session, the students are transported to their accommodations. The laboratory safety instruction takes place either at this point or on Day 3.

Day 3

An excursion is offered, and all the students must take part in the excursions. Students who are ill must either be taken to a hospital or constantly supervised by a representative of the host.

Day 4

Day 4 is the day of the Practical exam. During the exams, English copies of the exams should be available for students if there is any ambiguity in their translated version.

Day 5

Day 5 contains an excursion. Most students will also want to study for the theoretical exam. However, all the students must take part in the excursions, with the exception noted above in the case of illness or accident.

Day 6

Day 6 is the day of the Theoretical exam. During the exams, English copies of the exams should be available for the students.

Day 7

Day 7 includes an excursion, and it is possible to combine this excursion with that of the mentor excursion.

Day 8

Day 8 also includes an excursion.

Observers and Guests Program

Observers and guests typically follow the same excursion schedule as the mentors, although additional excursions may be organized for the guests during the times when the mentors and observers are busy with various parts of the exam (translation, discussion with authors, etc.).

Sample Documents

Sample 1 (Example of letter confirming the contact information for a particular country)

Sample 2 (Example of IChO Invitation Letter)

Sample 3 (Example of Registration Form for a country)

Sample 4 (Example of Registration Form for Mentors and Observers)

Sample 5 (Example of Registration Form for Students)